Adolescence is nothing if not an endless series of paradoxes. For the seasoned COVEN consumer – this phrase, being the inaugural line of COVEN Berlin’s Axe Pulse delineation, likely rings a bell. Yet, despite encountering this musing months ago, it was not until broaching an exploration of D’orjay The Singing Shaman’s (they/them) craft and life that it crystallised for me – the unanticipated synchronicity of pride, pubescence and shamanism it enclosed. Just as a shaman speaks and lives by paradox and cyclical approaches, honouring all polarities, we, as queers, may take liberties to reify teenagedom as not just a U.S. post-war convivial construction but rather a state of mind – accessed and abandoned at will. Perhaps, existing as queer folks do, teetering on the margins of acceptability, we mediate with more ease the elasticity of teenagedom as a potentiality which does not dissipate at the turn of a generation.

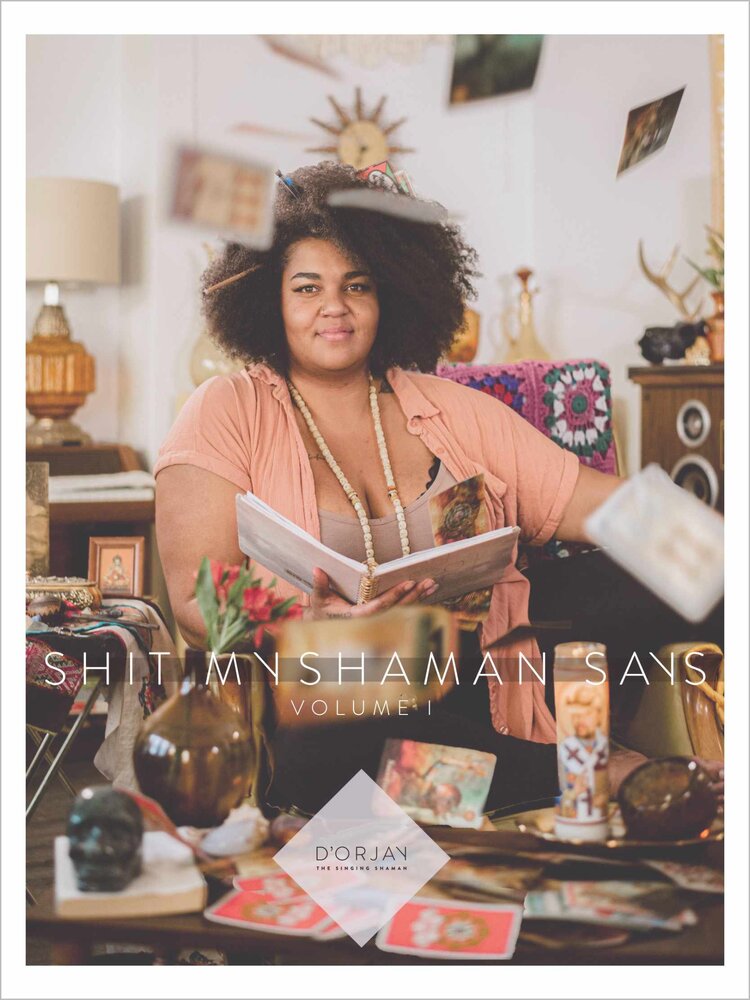

It was in 2020 when D’orjay, debuting Shit My Shaman Says: Volume I, a work Axe Pulse agnate in its anti-linear subversiveness, first came upon my newsfeed. I paused my lackadaisical scrolling – a professional shaman, singer, author, a partner and a cat parent – could one person really be so much?

The answer appeared affirmative, as D’orjay eschewed the dreaded sophomore slump, their literary debut battening, becoming a multi-volume handbook that, in navigating mental disorder, love and parental relationships, strives towards spiritual hygiene, healing and self-realisation. Although the concept gestated in D’orjay’s consciousness for a while – “I have a running list of books, stand-up comedy sketches, and lyrics in my phone,” they inform me during one of our two all too hasty Zoom calls – D’orjay credits Party Trick Press e-publisher founders Natahna Bargen-Lema and Megan Fedorchuk as the instigators of this rolling collaboration. Three volumes later, with yearly launches, Shit My Shaman Says – is characterised by its pithy lessons, with D’orjay, as guide and facilitator, imploring that amid our respective spiritual journeys, we nurture ourselves and unpack our shit, all the while sustaining stowage to sway with our subliminals and dally – guardians (spiritual and otherwise) in tow – amongst our devils. Penning their introduction to Volume One, D’orjay elucidates, “I wanted to create an efficient and easy-to-use handbook with tricks of the trade I’ve picked up over the years for when shit is hitting the fan and you need redirection fast.”

“I wanted to create an efficient and easy-to-use handbook with tricks of the trade I’ve picked up over the years for when shit is hitting the fan and you need redirection fast.”

– D’ORJAY THE SINGING SHAMAN, SHIT MY SHAMAN SAYS VOLUME I.

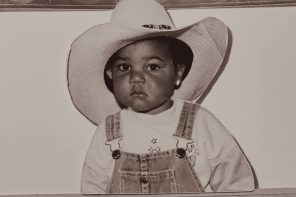

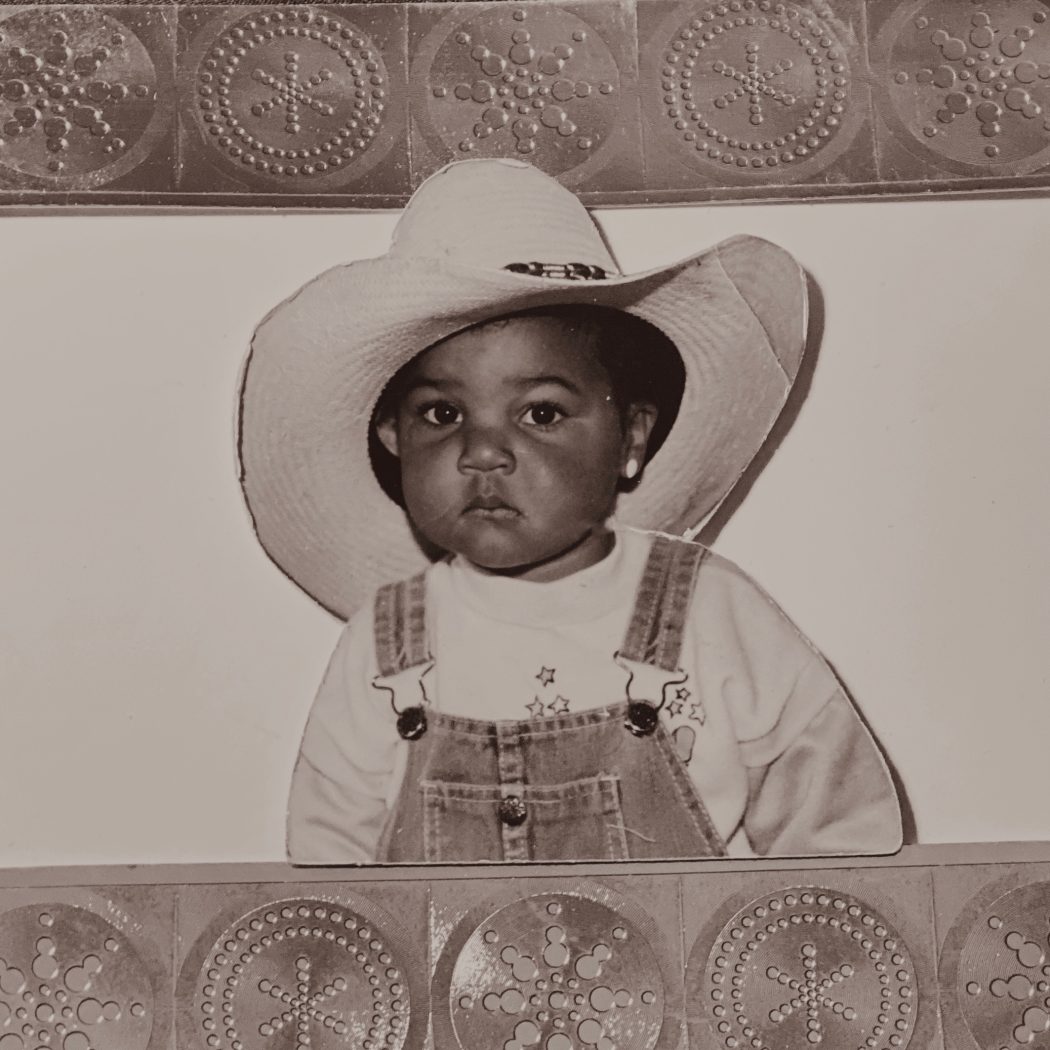

As to D’orjay’s personal reintegrative journey, reaping the knowledge necessary to reparent themselves, address attachment styles and practise by practise, burrow closer to the root of their trauma and the route of their desire, it was a winding and, recurrently, nebulous path. Moons ago, appetent for self-sabotage, D’orjay’s landscape fawned in metronomes of parental abandonment and childhood sexual trauma. As we learn within their writings, they waged depression and suicidal ideation, scoured Craigslist’s casual encounters section and manoeuvred terrestrials maudlin with red flags, love bombers and satisficing.

Wishing to self-correct and remove themselves from these toxic cycles, D’orjay, in 2010, turned to energy medicine, shamanic and pranic healing. The next five years would see D’orjay pilgrimage to myriad sacred sites, from the ‘Golden Summit’ and the Leshan Giant Buddha to the Tsar Tsar Monastery (Ashduk Derge Country, Eastern Tibet), their Guru’s, His Holiness Rimay Gyalten Sogdzin Rinpoche’s, Tibetan centre. Reflecting on this odyssean juncture, D’Orjay mused, “We would find ourselves on the tops of mountains that took us half a day to travel up. And that’s assisted travel. Then, coming up 100 to 200 feet, there would be gold statues and temples at the very top of this mountain. I was thinking a lot about the miraculousness of human beings in what we are capable of. How much more magic practice there seemed to have been back then.”

Journeying down to Joshua Tree in the Californian desert, D’orjay formally initiated their shamanic training with the Dr Alberto Lodos programme and the Four Winds Society, from which, in 2015, they became a full mesa carrier. The title, stemming from Mesa, meaning altar, signifies an individual willing to do the work and to aid others in their intentions, one rooted by a spiritual animus and awareness of the abundance within this plane, wary of voyeuristic, worldly inter-logics. More plainly put, D’orjay had become a qualified shaman.

“We would find ourselves on the tops of mountains that took us half a day to travel up. And that’s assisted travel. Then, coming up 100 to 200 feet, there would be gold statues and temples at the very top of this mountain…”

– D’ORJAY THE SINGING SHAMAN.

With any case of Western engagement with Eastern spirituality, it imposes to identify where the jackboot falls, yet, asinine profit and disregard for practice origins are relatively decisive doxxers of co-option versus celebration. D’orjay is steadfast, standing adversary to the late capitalist Swift-scape (Jonathon, not Taylor) we simulate. As a shaman, D’orjay facilitates flexible payment, and trade, tying several sessions to tithe and goodwill. “I am paying it forward. People struggle and need healing, but the financial aspect makes it inaccessible for many.” As an author, they act analogously, ensuring their work is accessible not only financially but also educationally – each volume of Shit My Shaman Says is offered at a sliding scale between low, medium and high, the eventual selection having no differentiation in the consequent corral. Reflecting on this desire for knowledge equity inherent to the project structure, D’orjay divests, “I am neurodivergent – I have ADHD. So, if I consider myself, when reading, I have to reread everything three to four times before I can fully digest and comprehend it. It was intentional to create something digestible and offer these easy reads, exercises and processes you could guide yourself through.”

While, perhaps, the capacity of integrative healing to reveal the entirely unforeseeable should cease to surprise, the sequelae of spiritual reconstruction jolted D’orjay. “I was sure I would qualify, return and help heal the world – that was the idea.” They relay. Yet Spirit, as D’orjay would designate that hyper-object, occult motivator, had other plans. Enfolded within the Chilean Jungle, nearing the culmination of their shamanic training, D’orjay espoused the revelation that, in line with direct shamanic work, the arts, particularly song, were, equitably, essential to their general convalescence and spiritual-creative vision. “Self-realisation is a cornerstone of becoming a facilitator for other people. Doing your work is the biggest piece enabling you to be a proficient facilitator for others to find their healing. I realised to restore those parts of my soul in the shadows and to fulfil this soul contract with the younger version of myself. I had little choice but to make this happen for myself.”

Actualising this spiritual download, in November 2020, D’orjay released their debut album, New Kind Of Outlaw. Sporting tracks such as “Float On (I Choose Me)” and “Soul Retrieval,” D’orjay waxes with the ecstasy of a dormant dream, liberated to fruition and perception. They note – “The biggest part about releasing the album was doing something for myself that truly contributed to my evolution. I am honouring myself and my relationship with my life, working toward not censoring or repressing myself.”

The biggest part about releasing the album was doing something for myself that truly contributed to my evolution. I am honouring myself and my relationship with my life, working toward not censoring or repressing myself.”

– D’ORJAY THE SINGING SHAMAN.

Like most of their clients, readers and listeners, I feel a mutuality with D’orjay, that they, throughout their life, have been similarly seeking a supposed happy medium between many things: the untempered and the tamed and the aid of the self and other being the two perhaps most palpable to their audience. Foreseeable to many of us, there is at the fulcrum of their teachings the oft-reiterated, more challengingly accomplished capsule: that selfishness, the privilege guiltless only to a very particular brand of teenager and more junior, is, non-negotiably, the currency of change. They write, “Only from a place of wholeness can we offer our gifts of service to others.” Archetypically speaking, rather than a guilty inner child, crying for confirmation of worth, or the fatalistic adult, we must become: the wilful pubescent. Continuing, D’orjay reassures — “Let your cup overflow first, then share from that abundant place. Easier said than done-trust me, I know!”

Words by Maedbh Pierce.

______________________________________________________________________________

Writer Bio

Currently studying an MA in Journalism, Media and Globalisation, Maedbh Pierce (she/her) is an English and Philosophy graduate (UCD, Dublin) and freelance writer. To date, her writing explores and celebrates queer identity, life and culture. Amongst others, her work has been featured in Unicorn Magazine, Shameless Magazine, Nonchalant London, and The Single Supplement. Find her on Instagram or LinkedIn.